Picture attributes to: https://kaiserscience.wordpress.com

Prologue: The Tapestry of Time

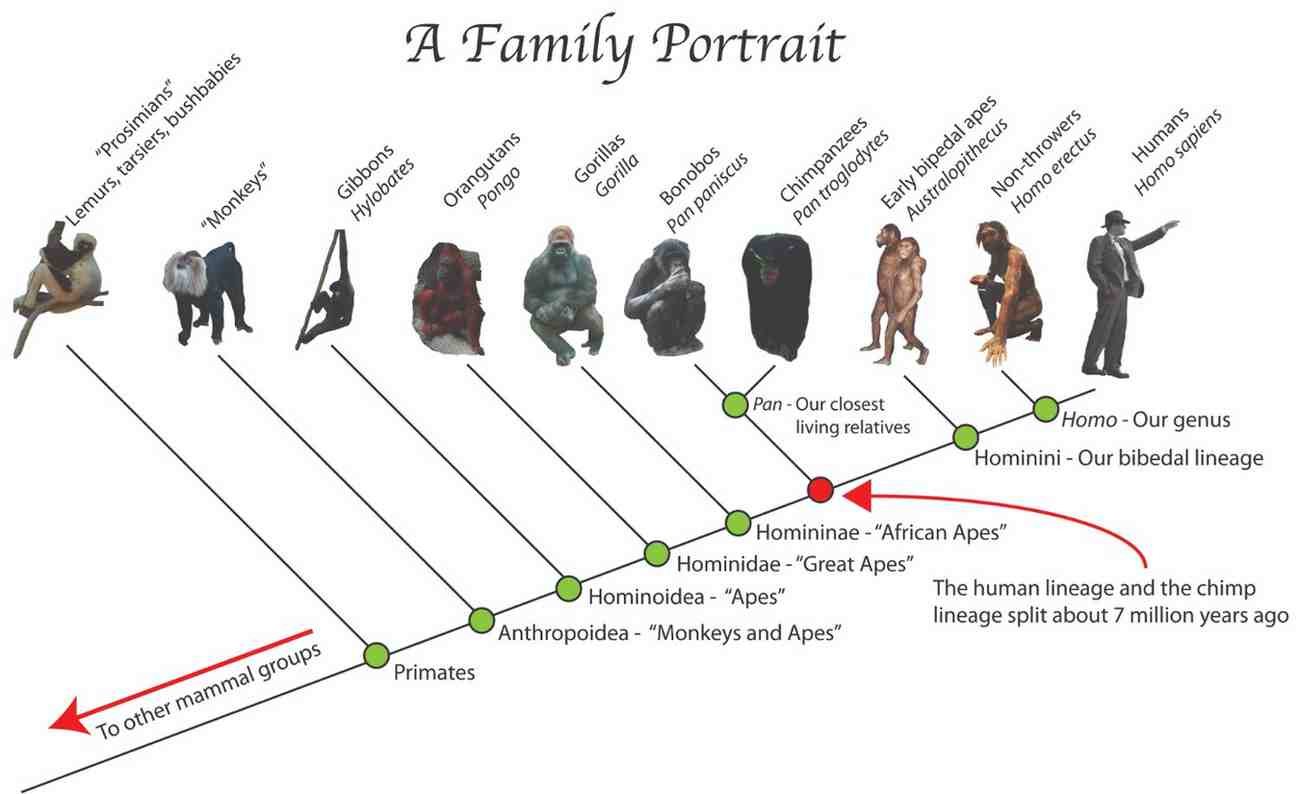

To understand the story of humanity is to undertake the most profound of journeys—a voyage back through the deep, abyssal stretches of time. It is a narrative written not in ink, but in stone, in bone, and in the very genetic code that defines us. This is the story of how a lineage of African primates, navigating the shifting sands of climate and ecology, gradually became something entirely new: a creature that walks upright, wields fire, shapes its world with tools, and gazes at the stars with questions about its own origin.

This 100,000-word exploration is not merely a chronological list of fossil discoveries. It is an attempt to weave together the threads of paleontology, genetics, climatology, and archaeology to create a rich tapestry of our becoming. We will meet our ancient cousins, some of whom are direct ancestors and others who are fascinating offshoots on the great tree of life, now long extinct. We will witness the crucible of climate change that forged our ancestors’ most defining traits. We will follow them out of Africa to populate every continent on Earth. This is the epic of us, Homo sapiens, from our humble beginnings in the verdant forests of a lost world to the species that now holds the future of the planet in its hands.

Part I: The Primate Foundation (c. 65 – 25 Million Years Ago)

Chapter 1: The World of the Early Primates

The story begins not with apes, but with the aftermath. Approximately 65 million years ago (mya), the catastrophic extinction event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs opened ecological niches for mammals to flourish. Among them were small, insectivorous, tree-dwelling creatures that would become the progenitors of all primates. Key fossils like Purgatorius, a small mammal from the late Cretaceous/early Paleocene, hint at the features that would define the order: grasping hands with nails instead of claws, forward-facing eyes for depth perception, and larger brains relative to body size.

For tens of millions of years, our ancestors evolved in a world of lush, global tropical forests. They were arboreal specialists. Their diet shifted from insects to include fruits and leaves, requiring dental and digestive adaptations. Social structures began to form, necessitating greater intelligence for navigating complex relationships. This period of stability and arboreal life laid the essential groundwork: the primate brain, binocular vision, and dexterous hands.

Chapter 2: The Hominoid Divergence: Apes Emerge

By the Oligocene epoch (around 34-23 mya), the primate family tree had branched significantly. One critical branch was the anthropoids, which included monkeys and apes. A key site for understanding this divergence is the Fayum Depression in Egypt, which 30-35 million years ago was a lush rainforest. Here, fossils of early anthropoids like Aegyptopithecus (“Egyptian ape”) have been found. It was likely a tree-dwelling, fruit-eating creature about the size of a modern gibbon, possessing a monkey-like body but with anatomical hints of the ape lineage to come.

The true apes, or hominoids, began to diversify in the Miocene epoch (23-5.3 mya). This was the golden age of apes. While monkeys were successful, the apes radiated into a wide variety of forms, spreading across Africa, Europe, and Asia. They were larger, more intelligent, and many abandoned tailes, developing a more upright posture for life in the trees, suspending from branches rather than running along the top of them. Famous Miocene apes include:

- Proconsul (23-25 mya, Africa): Considered a basal ape, it had a mix of monkey and ape traits—no tail, but a monkey-like body plan. It likely moved quadrupedally through the trees.

- Dryopithecus (12-9 mya, Europe): A European ape that showed adaptations for suspensory, arm-swinging locomotion.

- Sivapithecus (12.5-8.5 mya, Asia): This ape is a likely ancestor of the modern orangutan, showing clear facial similarities.

This great ape radiation was made possible by the warm, wet climates of the early Miocene. But change was on the horizon. The world was cooling, and the dense forests were beginning to recede.

Part II: The Hominin Breakaway (c. 10 – 4 Million Years Ago)

Chapter 3: The Crucible of Climate Change

The story of humanity is inextricably linked to the story of the African climate. Starting in the late Miocene (around 10 mya), tectonic shifts, including the uplift of the Himalayas and the East African Rift Valley, began to alter weather patterns. The global climate cooled and dried. In Africa, the vast evergreen forests fragmented, giving way to open woodlands and, eventually, savannahs—expanses of grassland with scattered trees.

This ecological crisis was a evolutionary catalyst. For the apes of Africa, it was a disaster. Their specialized arboreal lifestyle and fruit-based diet became a liability. The lush, continuous canopy was gone. This environmental pressure forced a dramatic adaptive shift. One lineage of apes began to spend more and more time on the ground. This was the moment of divergence—the split between the line that would lead to chimpanzees and bonobos, and the line that would lead to us: the hominins.

Chapter 4: The First Hominins: Upright Walking

The defining adaptation of the earliest hominins was not a big brain or tool use, but bipedalism—walking upright on two legs. The advantages in this new environment were clear:

- Energy Efficiency: Bipedalism is more efficient than a chimp-like crouch for covering long distances between patchy food sources.

- Thermoregulation: Standing upright exposes less body surface area to the intense equatorial sun and raises the body higher above the hot ground.

- Carrying and Foraging: Freeing the hands allowed for carrying food back to a home base or family group, and for manipulating objects.

The evidence for this shift is found in some of the most celebrated fossils in paleontology:

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7-6 mya, Chad): represented by a nearly complete skull nicknamed “Toumaï.” Its foramen magnum (the hole where the spinal cord enters the skull) suggests it held its head upright, a strong indicator of bipedalism. It lived close to the time of the chimp-human split.

- Orrorin tugenensis (6 mya, Kenya): Known from fragmentary remains, including a femur that exhibits anatomy consistent with walking upright.

- Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4 mya, Ethiopia): “Ardi” provided a revolutionary snapshot. She was a biped on the ground but still a capable climber in the trees, with an opposable big toe. She showed that early hominins did not evolve from a knuckle-walking chimp-like creature; instead, both lineages evolved from a more generalized, Ardipithecus-like ancestor.

Chapter 5: The Australopithecines: The Adaptive Radiation

Following the Ardipithecus pioneers came a highly successful and diverse group of hominins known as the australopithecines (“southern apes”). They flourished from about 4.2 to 1.9 mya. They were not yet human, but they had fully committed to bipedalism, as evidenced by their famous fossils:

- Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) (3.9-2.9 mya, East Africa): The 40%-complete skeleton discovered in 1974 provided undeniable proof of a small-brained, fully bipedal hominin. Her pelvis, knees, and feet were human-like, but her brain was chimp-sized (~385-550 cc), and she had long arms and curved fingers for climbing.

- The Laetoli Footprints (3.66 mya, Tanzania): Preserved in volcanic ash, these footprints of two A. afarensis individuals walking side-by-side provide a breathtaking snapshot in time, proving unequivocally that our ancestors walked upright with a striding gait millions of years ago.

The australopithecines were not a single species but a adaptive radiation, experimenting with different diets and lifestyles in the mosaic environments of Africa:

- Gracile Australopithecines (e.g., A. africanus): More lightly built, likely omnivorous.

- Robust Australopithecines (Paranthropus, e.g., P. boisei, “Nutcracker Man”): Evolved massive jaws, huge molars, and sagittal crests on their skulls for powerful chewing muscles to process tough, fibrous vegetation. They were a specialized side branch that eventually went extinct.

They were successful for millions of years, but they were ultimately a conservative group. Their tool use was likely minimal and no more advanced than that of modern chimps. The next great leap would come from within their ranks.

Part III: The Genus Homo: The Brain and Tool Revolution (c. 2.5 – 1.5 Million Years Ago)

Chapter 6: Homo habilis: The Handy Man

Around 2.4 mya, the climate entered a period of intense instability and aridity. The savannahs expanded further. This presented new challenges and opportunities. In this crucible, a new genus appeared: Homo.

The first representative is Homo habilis (“handy man”), named by Louis and Mary Leakey based on fossils found at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, alongside the oldest known stone tools. Homo habilis was a significant departure from the australopithecines:

- Brain Size: Its cranial capacity (~550-687 cc) was notably larger than that of any australopithecine.

- Teeth and Jaw: It had smaller teeth and a less protruding face, suggesting a shift to a higher-quality diet that included more meat, likely from scavenging.

- Technology: It was the first consistent maker of stone tools, the Oldowan industry. These were simple choppers, flakes, and cores, but they represented a cognitive leap—the ability to visualize a tool within a stone and to strike it in a specific way to create a sharp edge. This technology allowed access to nutrient-rich marrow and meat, fueling the evolution of a larger, more energy-demanding brain.

Chapter 7: Homo erectus: The Game Changer

If Homo habilis was the innovator, Homo erectus (“upright man”) was the pioneer who changed everything. Appearing around 2 mya in Africa (where early specimens are sometimes called H. ergaster), H. erectus was the first hominin to truly look human-like in its body proportions.

Its adaptations were revolutionary:

Body Plan: It was tall and slender, with long legs and short arms, a build perfectly adapted for long-distance walking and running (persistence hunting) in the hot, open savannah. The skeleton of the “Nariokotome Boy” (1.5 mya) shows a modern stature.

- Brain Expansion: Its brain size (~600-1100 cc) showed a dramatic increase, overlapping with the lower range of modern humans.

- Technology: It developed the more sophisticated Acheulean tool industry, characterized by iconic, symmetrical, bifacial hand-axes. These were not just tools; they were the first multi-purpose implements, designed to a mental template and curated over time.

- The Taming of Fire: While debated, evidence suggests H. erectus was the first hominin to systematically control fire (by at least 1 mya, with stronger evidence from 400,000 years ago). Fire provided warmth, protection from predators, and, crucially, cooking—which made food safer, easier to digest, and more nutritious, further fueling brain growth.

- Out of Africa: Most astonishingly, Homo erectus was the first hominin to leave Africa, spreading across Asia (as evidenced by fossils in Dmanisi, Georgia at 1.8 mya, and Java, Indonesia) and Europe. This migration was one of the most significant events in human prehistory.

Homo erectus was incredibly successful, persisting for over 1.5 million years. It set the template for all later hominins.

Part IV: The World Before Us: Archaic Humans (c. 800,000 – 300,000 Years Ago)

Chapter 8: A Crowded World

As Homo erectus populations spread and became isolated across the vastness of the Old World, they began to evolve into distinct regional forms, often classified as “archaic humans.” This period is complex, with multiple species overlapping in time and space.

- In Europe: Homo heidelbergensis (600-200 kya) is considered a likely common ancestor to both Neanderthals and modern humans. They were robust, large-brained (~1100-1400 cc), and skilled hunters of big game. They built simple shelters and may have had early symbolic or ritualistic behaviors.

- The Road to Neanderthals: In Europe, H. heidelbergensis gradually evolved into the classic Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), who were supremely adapted to the harsh Ice Age climates of Europe and western Asia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Chapter 9: The Neanderthals: Our Closest Cousins

Neanderthals have been unfairly characterized as brutish and stupid. Science has revealed a very different picture. They were a highly intelligent, sophisticated, and powerful human species.

- Physical Adaptations: They had a stocky, muscular build to conserve heat, large noses to warm cold air, and a brain that was, on average, slightly larger than that of modern humans.

- Culture (Mousterian Tool Industry): They were master toolmakers, creating sophisticated flake tools using the Levallois technique, which required advanced planning.

- Hunting: They were apex predators, taking down massive prey like mammoths and woolly rhinos in close-quarter ambushes, a testament to their courage and strength.

- Symbolism and Care: Evidence suggests they buried their dead, sometimes with grave goods like flowers and tools. They used pigments, wore ornaments, and cared for their sick and injured, indicating complex social bonds and perhaps the of symbolic thought.

For a time, two species of humans shared the same world.

Part V: The Rise of Homo sapiens (c. 300,000 – 50,000 Years Ago)

Chapter 10: The Origin of Our Species in Africa

While Neanderthals dominated Europe, the story of our own species, Homo sapiens, was unfolding in Africa. The oldest known fossils that are classified as anatomically modern humans come from sites in Morocco (Jebel Irhoud, ~300 kya), Ethiopia (Omo Kibish, ~200 kya), and South Africa (Florisbad, ~260 kya).

These early Homo sapiens had a modern skeletal structure: a globular skull, a high forehead, a reduced brow ridge, and a chin. But for the first 100,000 years of our existence, our behavior remained relatively conservative, similar to that of Neanderthals and H. heidelbergensis.

Chapter 11: The Great Leap Forward: Behavioral Modernity

Sometime between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, something remarkable happened. There was a cultural “big bang” in Africa. The archaeological record reveals an explosive emergence of what we call behavioral modernity:

- Sophisticated Art: Cave paintings (like those at Blombos Cave, South Africa), intricate engravings on ochre, and personal adornment like shell beads.

- Complex Technology: Smaller, more standardized blade tools, the invention of projectile weapons like spear-throwers and eventually bows, and the use of new materials like bone and antler.

- Symbolic Language: The art and adornment point to a complex symbolic capacity, almost certainly underpinned by fully modern, syntactical language. This allowed for the communication of complex ideas, the formation of intricate social structures, and the transmission of culture with unprecedented fidelity.

The reasons for this leap are hotly debated: a genetic mutation related to cognition, the development of complex language, or a slow buildup of cultural innovations that finally reached a critical mass.

Chapter 12: The Second Migration: Conquering the World

Empowered by this new cognitive and cultural toolkit, Homo sapiens began a second major migration out of Africa around 70-60,000 years ago (though earlier, failed migrations likely occurred). This time, the species that left was fundamentally different. We were not just another hominin; we were an insurmountable force of innovation and adaptability.

We spread rapidly along coastlines, reaching Australia by 65,000 years ago (a journey requiring ocean voyages) and Europe by 45,000 years ago. In Europe, we encountered the Neanderthals.

Part VI: The Human Planet (c. 50,000 – 12,000 Years Ago)

Chapter 13: The Fate of the Other Humans

The arrival of Homo sapiens in Eurasia coincided with the disappearance of all other hominin species. The Neanderthals vanished around 40,000 years ago. Other groups like the Denisovans in Asia and the “hobbits” (Homo floresiensis) on Flores Island also went extinct.

The cause is one of paleontology’s greatest mysteries. It was likely a combination of factors:

- Competition: Homo sapiens, with its superior technology, social organization, and hunting strategies, may have outcompeted other species for resources.

- Climate Change: Oscillating Ice Age climates put stress on all populations.

- Absorption: Genetic evidence proves there was interbreeding. Non-African modern humans carry small percentages of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA, proving that these groups met and had children together. They are not entirely extinct; they live on in us.

Chapter 14: The Zenith of the Hunter-Gatherer

For the next 30,000 years, Homo sapiens perfected the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. We created breathtaking art in caves like Chauvet and Lascaux. We crafted exquisite tools and clothing. We developed rich spiritual beliefs and complex social networks that spanned continents. Our population grew, and we adapted to every environment on Earth, from the Arctic tundra to the Amazon rainforest. This period represents over 95% of human history and shaped our fundamental psychological and social nature.

Chapter 15: The Final Frontier: The Americas

The last continents to be populated were the Americas. As the Last Glacial Maximum locked up water in ice sheets, sea levels dropped, exposing a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska known as Beringia. Around 16-20,000 years ago (possibly earlier), bands of hunter-gatherers followed migrating herds across this bridge or traveled along the coast by boat. They then spread with incredible speed down the ice-free corridors of North America and into the vast, empty continent of South America, reaching its southern tip within a few thousand years.

Part VII: The Modern World: Revolution and Conquest (12,000 Years Ago – Present)

Chapter 16: The Neolithic Revolution: Taming Nature

The end of the last Ice Age around 11,700 years ago brought a warmer, more stable climate. In several regions around the world—the Fertile Crescent, China, Mesoamerica, the Andes—humans began to transition from foraging to farming. This Neolithic Revolution was the most profound lifestyle change since the discovery of fire.

- Domestication: Humans began to deliberately plant seeds (wheat, barley, rice, maize) and tame animals (goats, sheep, cattle).

- Sedentary Life: Farming led to permanent settlements, which grew into villages, then towns, and eventually the first cities.

- Consequences: This led to a population explosion, the accumulation of wealth, social stratification, specialized labor, and the invention of new technologies like pottery, weaving, and metallurgy. It also introduced new problems: social inequality, zoonotic diseases, and environmental degradation.

Chapter 17: The March of Civilization

From these agricultural hearths, civilization emerged. Writing was invented to keep records. Laws were codified. Monumental architecture, like pyramids and ziggurats, was built. Empires rose and fell. The pace of change, which had been glacial for millions of years, began to accelerate exponentially.

Chapter 18: The Age of Exploration and Globalization

The innate human drive to explore, which had led us out of Africa, continued. Civilizations made contact, trading goods, ideas, and, unfortunately, diseases and conflict. The European colonization of the world after 1492 CE was a biological and cultural cataclysm on a scale not seen since the meeting of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, reshaping global populations and ecologies forever.

Chapter 19: The Scientific Age and Understanding Our Past

The final chapter in our evolutionary story is the one in which we discovered the story itself. The development of science, geology, and ultimately genetics and paleontology in the last few centuries allowed us to piece together our own deep history. We dug up the fossils of our ancestors, sequenced the DNA of modern and ancient humans, and finally began to understand our true place in the natural world—not as a special creation, but as the current product of a long, unbroken, and magnificent evolutionary journey.

Epilogue: The Future of Homo sapiens

From a humble primate navigating the treetops to a species that has walked on the moon and decoded its own genome, the journey of human development is a testament to the power of adaptation, innovation, and cooperation. Our evolution did not stop with the advent of civilization; it merely changed form. Cultural evolution now operates at a pace that dwarfs biological evolution.

We now face challenges of our own making: climate change, resource depletion, and the potential misuse of our own powerful technologies. The same brain that mastered fire and built civilizations now holds the power to destroy them. The story of human development is not over. The question is no longer where we came from, but where we, the wise ape—Homo sapiens—will choose to go next. The next chapter is ours to write.