Picture attributes to: suronin / Shutterstock.com

The architecture of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), or Harappan Civilization, represents one of the world’s first and most sophisticated urban planning paradigms. Unlike its contemporaries in Mesopotamia and Egypt, which expressed architectural grandeur through monumental temples and palaces, Harappan architecture is distinguished by its egalitarian, utilitarian, and meticulously planned character. It reflects a highly organized, centralized socio-political system with an exceptional emphasis on hygiene, water management, and standardisation. This analysis delves into the principles, typologies, construction technologies, and socio-cultural implications of this unique architectural tradition.

1: Introduction to the Indus Valley Civilization and its Architectural Context

1.1. Chronological and Geographical Framework

- Early Harappan (c. 3300 – 2600 BCE): Pre-urban phase with nascent settlement patterns, beginning of craft specialisation, and early forms of the defining ceramic styles. Architecture consists of simple mud-brick structures.

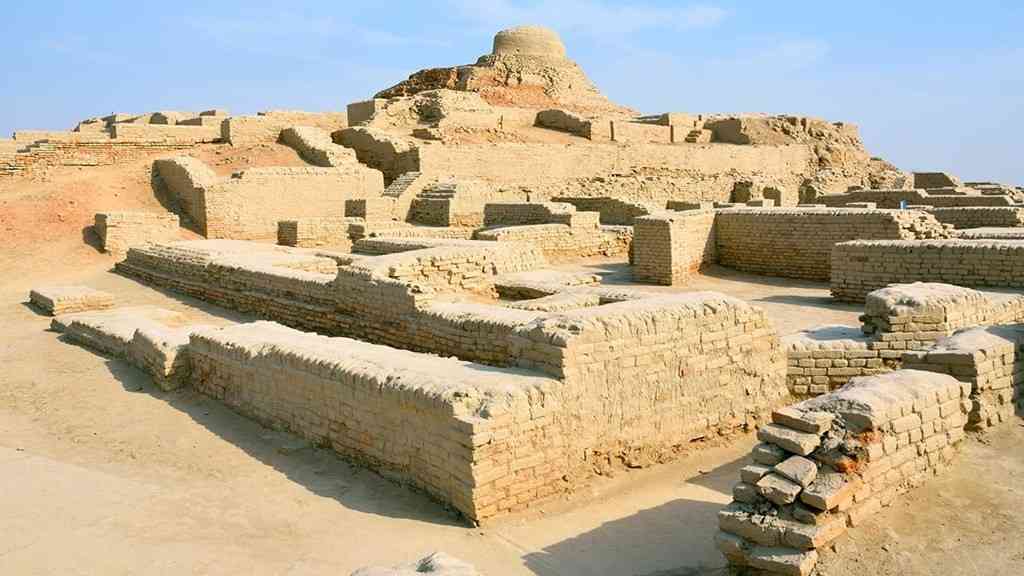

- Mature Harappan (c. 2600 – 1900 BCE): The zenith of urbanism. The characteristic grid-plan cities of Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira, etc., were built and flourished. This period is the primary focus of architectural study.

- Late Harappan (c. 1900 – 1300 BCE): Period of de-urbanisation, abandonment of major cities, and a shift towards rural settlements and regional cultures. Architectural standards decline, and the integrated system breaks down.

1.2. Sources of Evidence and Archaeological History

Excavation History: From the initial discoveries at Harappa (1921) and Mohenjo-daro (1922) by Daya Ram Sahni and R.D. Banerji, to the extensive work of Sir John Marshall, M.S. Vats, and E.J.H. Mackay. Later, work by George F. Dales, J.M. Kenoyer, R.S. Bisht, and numerous Indian and international teams has expanded our understanding.

Key Sites Providing Architectural Data:

- Mohenjo-daro (Sindh, Pakistan): The “Mound of the Dead,” largest site, reveals extensive urban planning.

- Harappa (Punjab, Pakistan): The type-site, though heavily damaged by 19th-century brick robbing.

- Dholavira (Gujarat, India): Unique for its sophisticated water management and ceremonial grounds.

- Lothal (Gujarat, India): Famous for its suspected dockyard and warehouse.

- Kalibangan (Rajasthan, India): Shows both Early and Mature Harappan phases with a pre-Harappan fortification.

- Surkotada, Banawali, Rakhigarhi, Ganweriwala among others.

1.3. Defining Characteristics of Harappan Architecture

Standardisation: Use of standardised bricks (ratio 1:2:4 for thickness:width:length) across the entire civilization, spanning over a million square kilometers.

Orthogonal Grid Planning: Streets and lanes laid out in a precise north-south, east-west grid pattern.

Focus on Hygiene and Water Management: The most defining feature, exemplified by the elaborate Great Bath, numerous wells, and the sophisticated drainage system.

Absence of Monumental Royal or Religious Structures: No definitive palaces, large temples, or grand tombs have been identified, suggesting a different power structure than contemporary civilizations.

2: Foundational Principles and Urban Planning

2.1. The Concept of the Citadel and Lower Town

This is the most prevalent urban model in major Harappan cities.

The Citadel (Upper Town):

- A massive mud-brick platform, often reinforced with retaining walls, artificially raised above the flood plain.

- Function: Likely an administrative, religious, and elite residential centre. It housed structures of civic importance (Great Bath, Granaries, Pillared Halls).

- It was physically separated from the Lower Town, either by walls, space, or elevation, implying a socio-functional hierarchy.

The Lower Town:

- The extensive residential and commercial sprawl where the majority of the population lived.

- Laid out in a rigid grid pattern, it was densely packed with houses, workshops, and markets.

2.2. Fortifications and Defensive Architecture

- Purpose: Contrary to earlier beliefs of a peaceful civilization, most major sites were fortified.

- Features: Massive walls with square bastions or rounded salients constructed of mud-brick or fired brick. Gates were strategically placed and often controlled access. Dholavira’s fortifications are the most elaborate, with multiple castles, baileys, and enclosures.

2.3. Street Planning and Circulation

Grid Iron Pattern: The cardinal orientation of streets created city blocks, improving organization, drainage, and wind circulation.

Hierarchy of Streets: A clear hierarchy existed:

- Major Streets: Wide (up to 10m+), running north-south and east-west, dividing the city into large blocks.

- Secondary Lanes: Narrower streets branching off the main arteries.

- Alleys and Paths: Small, unpaved access ways between individual compounds.

Street Furniture: Corners were rounded to allow easy movement of carts. Drains ran alongside streets.

3: Architectural Typologies and Structures

3.1. Residential Architecture

The Courtyard House Plan: The fundamental unit of Harappan domestic architecture.

- Layout: Houses were inward-looking, built around a central courtyard which provided light, ventilation, and privacy.

- Rooms: Multiple rooms opened onto the courtyard. Houses often had two stories, with staircases leading to the upper floor or roof.

- Privacy: Windows and doors opened onto the inner courtyard, not the main streets, ensuring family privacy.

Building Materials:

- Bricks: Standardised sun-dried (adobe) bricks for the majority of construction. Fire-burnt bricks were reserved for areas exposed to water (baths, drains, wells, fortification walls).

- Wood: Used for beams, lintels, doors, and staircases (evidenced by cavities and impressions).

- Other: Lime plaster and gypsum mortar were used for flooring and waterproofing.

Amenities:

- Wells: Many houses had their own private wells, a remarkable feature.

- Bathrooms: Almost every house had a bathing area with a finely laid brick floor, sloped towards a corner outlet.

- Latrines: Toilets were usually located on the ground floor, often on the street side of the house for easy connection to the main drain.

3.2. Civic and Public Architecture

The Great Bath (Mohenjo-daro):

- Description: The most famous Harappan structure. A large, waterproofed brick pool (12m x 7m x 2.4m) located on the citadel.

- Construction: Fine craftsmanship with tight brickwork, a thick layer of bitumen (tar) for waterproofing, and surrounded by corridors and rooms.

- Function: Likely had a ritual, purification-related function. It suggests the importance of water in Harappan ideology.

The “Granaries”:

- Mohenjo-daro: A massive brick foundation with alternating solid and hollow bays, believed to be a ventilated base for a large granary or storage facility.

- Harappa: A series of circular brick platforms, interpreted as bases for storing grain in straw bins.

- Interpretation: These structures signify centralised collection, storage, and redistribution of agricultural surplus, a key function of the ruling authority.

Pillared Halls and Assembly Buildings:

- Large open halls with rows of brick pillars (e.g., the “College of Priests” in Mohenjo-daro) are interpreted as spaces for public assembly, administration, or elite gathering.

3.3. Water Management Systems

This is arguably the pinnacle of Harappan engineering.

Drainage System:

- Covered Drains: Each house had small drains that emptied into larger, covered street drains made of brick.

- Design: Drains had corbelled arches and were laid below street level. They featured manholes and inspection traps for regular cleaning and maintenance—a concept far ahead of its time.

Water Collection and Storage:

- Wells: Numerous private and public wells were constructed with special wedge-shaped bricks to form a circular well shaft.

- Reservoirs (Dholavira): The site features a series of massive, rock-cut reservoirs on the eastern and southern sides of the city, channeling monsoon water and storing it for year-round use. This is the most sophisticated water conservation system of the ancient world.

3.4. Industrial and Commercial Architecture

- Workshops: Areas with kilns (for pottery, brick-making, faience), furnaces (for metalworking), and stone tool workshops have been identified within cities.

- The “Dockyard” at Lothal: A large, brick-lined enclosure connected to the river via a channel. Heavily debated, it is interpreted by many as a tidal dock for berthing ships and conducting trade, complete with a spillway and lock-gate system.

4: Construction Technology and Materials

4.1. Brick Technology and Standardisation

- Proportions: The consistent 1:2:4 ratio allowed bricks from different production batches and different cities to be used interchangeably.

- Manufacturing: Kilns at sites like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro show large-scale, organised production. Bricks were fired to a high temperature, making them extremely durable.

- Bonding Patterns: English bond (alternating courses of headers and stretchers) was commonly used, providing structural strength.

4.2. Foundations and Load-Bearing Walls

- Deep Foundations: Walls were founded on deep, hard-packed earth or rubble foundations to ensure stability, especially for large structures on the artificial citadel mounds.

- Massive Walls: Load-bearing walls were incredibly thick (often over a meter), designed to support heavy upper stories and roofs.

4.3. Roofing, Floors, and Waterproofing

- Roofs: Likely flat, made of wooden beams supporting reed matting or planks, covered with a layer of packed clay. Vaulting and corbelling were known but used primarily for drains.

- Floors: Typically made of compacted earth, but important rooms had floors of fired bricks set in gypsum mortar or a smooth, hard lime plaster called chunam.

- Waterproofing: Bitumen, a naturally occurring tar, was used to line the Great Bath and possibly other water tanks.

5: Regional Variations in Harappan Architecture

While sharing core features, architecture adapted to local environments.

Dholavira (Kutch, Gujarat):

- Built on rocky island, it could not dig deep wells. Instead, it developed the spectacular reservoir system.

- Used locally available stone alongside bricks.

- Featured a large, ceremonial ground and unique signboard.

Lothal (Gulf of Cambay, Gujarat):

- Built on a mound to protect against floods.

- Its alleged dockyard is its unique feature.

- Houses had central courtyards but were more densely packed.

Kalibangan (Rajasthan):

- Showed a double citadel.

- Provided the earliest evidence of a ploughed field.

- Had fire altars in some houses, suggesting specific ritual practices.

6: Interpretation and Socio-Political Implications

6.1. The Enigma of Power: Absence of Palaces and Temples

- The Problem: The lack of clearly identifiable royal palaces or large state temples challenges traditional models of early state power, which is often architecturally manifested.

Theories:

- Oligarchy/Council of Elders: Power may have been held by a group of elites (merchants, priests) rather than a single king, explaining the lack of a single palace.

- Ideological Focus: Power and ideology may have been centered on control of water, trade, and ritual purity (as seen in the Great Bath and granaries) rather than monumental personal glorification.

- Archaeological Bias: The uppermost levels of sites are heavily eroded. The most prominent structures may have been lost.

6.2. Social Organization as Reflected in Architecture

- Egalitarianism vs. Hierarchy: The uniformity in brick size, access to water and drainage, and similar house plans suggest a degree of social equity. However, the variation in house size (from single-room dwellings to large mansions with dozens of rooms) and the citadel/lower town division indicate a stratified society.

- Centralized Planning: The extreme standardization implies a powerful central authority with the ability to plan cities, enforce building codes, and organize labor on a massive scale.

6.3. Ideology and Worldview

- The Cult of Water: The architectural obsession with water—baths, drains, wells, reservoirs—suggests it held profound ritual and practical significance. Purification may have been a key ideological concept.

- Cosmological Alignment: The cardinal orientation of cities and major structures may reflect a cosmology aligned with the heavens, a common feature in ancient urban planning.

7: Decline and Legacy

7.1. Late Harappan Architectural Changes

As the civilization declined, the integrated system broke down:

- Breakdown of the grid plan; new structures were built over former streets.

- Decline in public sanitation; drains were blocked and fell into disuse.

- Use of smaller, non-standard bricks.

- Re-use of bricks from older structures.

7.2. Legacy on the Indian Subcontinent

While there is no direct, linear evolution, certain Harappan features persist in later traditions:

- Water Culture: The emphasis on ritual bathing may find an echo in the later Hindu ghats and temple tanks (pushkarini).

- Urban Planning: The concept of the citadel is seen in later historical cities.

- Domestic Architecture: The courtyard house remains the fundamental model of domestic architecture across South Asia to this day.

Conclusion: The Significance of Harappan Architecture

Harappan architecture is not about awe-inspiring monuments for the dead or the divine. Its monumentality lies in its sheer rationality, its profound understanding of hydraulic engineering, and its commitment to public welfare through urban planning. It represents the blueprint of a unique, highly complex society whose priorities were order, hygiene, and collective well-being, making it one of the most fascinating and enigmatic architectural achievements of the ancient world. Its study continues to challenge our preconceptions about early states and the relationship between power, society, and the built environment.