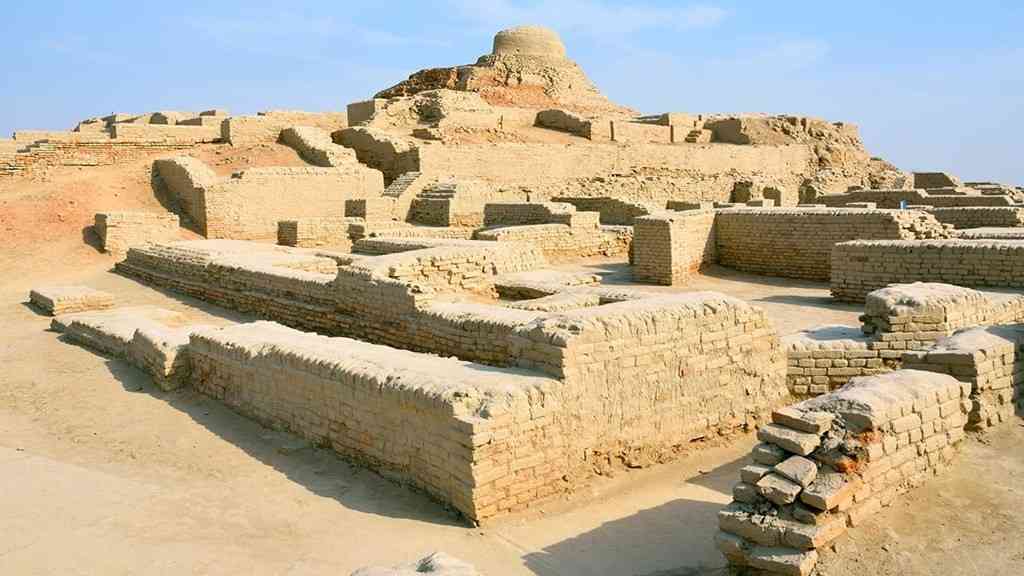

Picture attributes to: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Kot_Diji

1 Introduction to Pre-Harappan Architecture

The study of Pre-Harappan architecture provides crucial insights into the early development of urban planning and construction techniques that would later characterize one of the world’s earliest civilizations. The Pre-Harappan period, dating approximately from 3300 to 2600 BCE, represents a formative era in South Asian history when diverse regional cultures laid the groundwork for the subsequent rise of the mature Harappan civilization. This period, alternatively known as the Early Harappan or Regionalization Era, witnessed significant technological innovations, social transformations, and architectural experiments that would eventually coalesce into the sophisticated urban traditions of the Indus Valley Civilization.

The importance of Pre-Harappan architecture lies in its role as a transitional phase between earlier Neolithic villages and later urban centers. Unlike the relatively uniform architectural styles of the mature Harappan period, Pre-Harappan architecture displays remarkable regional diversity with distinct cultural variations across different zones of northwestern South Asia. These regional variations include the Amri-Nal culture in Baluchistan and southern Sindh, the Kot Dijian culture in northwestern Pakistan and northern Sindh, the Sothi-Siswal culture in northern Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab, and the Hakra culture in the Ghaggar-Hakra river system.

Archaeological investigations of Pre-Harappan sites have revealed how early communities gradually developed more complex settlement patterns, construction methods, and organizational structures. The architectural remains from this period demonstrate a progressive sophistication in building technology, including the development of mud-brick construction, the emergence of defensive fortifications, and the initial experiments with urban planning principles that would later become hallmarks of the mature Harappan cities. These developments did not occur in isolation but were part of a broader socioeconomic transformation involving the intensification of agriculture, the expansion of trade networks, and the specialization of crafts.

Understanding Pre-Harappan architecture is essential for comprehending the origins of South Asia’s urban tradition. The architectural innovations of this period established foundational elements that would be refined and expanded during the Integration Era (2600-1900 BCE) of the Indus Valley Civilization. By examining the structural remains, settlement patterns, and building technologies of Pre-Harappan communities, we can trace the evolutionary processes that led to the emergence of one of the ancient world’s most sophisticated urban civilizations.

2 Geographical and Chronological Context

The Pre-Harappan period encompasses a vast geographical area extending across what is now modern-day Pakistan and northwestern India. This region includes the mountainous zones of Baluchistan, the alluvial plains of Sindh and Punjab, and the dry river valleys of Rajasthan and Haryana. The chronological framework for this period has been established through extensive archaeological excavations and radiocarbon dating, which place the Pre-Harappan era between approximately 3300 BCE and 2600 BCE, though earlier antecedents can be traced back to 5000 BCE in some regions.

The geographical distribution of Pre-Harappan sites reveals a pattern of human settlement adapted to diverse ecological zones. In the mountainous regions of Baluchistan, sites such as Mehrgarh and Nausharo show evidence of early agricultural communities that gradually developed more complex architectural forms. The alluvial plains of the Indus and its tributaries hosted sites like Kot Diji and Amri, where communities benefited from fertile soils and developed irrigation technologies. In the eastern regions, along the now-dry Ghaggar-Hakra river system, sites such as Kalibangan and Banawali emerged as important centers with distinctive architectural traditions.

Chronologically, the Pre-Harappan period can be divided into several phases based on cultural and technological developments. The early phase (c. 3300-2800 BCE) is characterized by the emergence of distinct regional cultures with their own pottery styles and architectural traditions. The middle phase (c. 2800-2700 BCE) shows increasing cultural integration and the development of more standardized architectural forms. The late phase (c. 2700-2600 BCE) demonstrates clear trends toward urbanization, with the appearance of fortifications, planned settlements, and architectural elements that anticipate the mature Harappan period.

The transition from Pre-Harappan to mature Harappan was not uniform across all sites. Some settlements, such as Kot Diji and Kalibangan, show a clear stratigraphic break between the two periods, indicating possible disruption or abandonment. Other sites, including Amri and Harappa itself, demonstrate greater continuity with a gradual transition from Early to Mature Harappan phases. This varied pattern suggests a complex process of cultural development involving both indigenous evolution and external influences.

Table: Major Pre-Harappan Cultural Complexes and Their Characteristics

| Cultural Complex | Geographical Distribution | Time Period | Key Sites | Architectural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amri-Nal | Baluchistan, Southern Sindh | 3200-2600 BCE | Amri, Nal, Balakot | Mud-brick structures, some fortifications, distinctive painted pottery |

| Kot Diji | Northwestern Pakistan, Northern Sindh | 3200-2600 BCE | Kot Diji, Rahman Dheri | Fortified settlements, citadel and lower town division, mud-brick architecture |

| Sothi-Siswal | Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab | 3300-2600 BCE | Kalibangan, Siswal, Sothi | Mud-brick fortifications, residential structures, fire altars |

| Hakra | Ghaggar-Hakra River System | 3800-3200 BCE | Bhirrana, Kunal | Semi-subterranean dwellings, early mud-brick structures, storage pits |

3 Characteristics of Pre-Harappan Architecture

Pre-Harappan architecture exhibits several distinctive characteristics that reflect the technological capabilities and social organization of these early communities. Unlike the standardized architecture of the mature Harappan period, Pre-Harappan structures show significant regional variation while sharing certain common features that represent the beginnings of South Asia’s urban tradition.

The primary building material used in Pre-Harappan architecture was mud-brick, though stone and wood were also employed depending on local availability. Mud-bricks were typically manufactured in standardized ratios, often following a 3:2:1 proportion (30×20×10 cm at Kalibangan), which anticipates the uniform brick sizes of the mature Harappan period. These bricks were typically sun-dried rather than fired, though baked bricks began to appear in certain contexts such as drains and bathrooms at sites like Kalibangan. The use of burnt bricks for specific purposes like drainage systems represents an important technological innovation that would be greatly expanded in later periods.

One of the most significant architectural developments of the Pre-Harappan period was the emergence of fortification systems. Many sites, including Kot Diji, Kalibangan, and Amri, feature defensive walls surrounding settlements. At Kot Diji, a massive defensive wall constructed of stone and mud-brick with bastions protected the settlement. Similarly, at Kalibangan, the Early Harappan settlement was fortified with a mud-brick wall approximately 1.9 meters thick, which was later reinforced to between 3.7-4.1 meters. These fortifications suggest growing concerns with defense and possibly increasing social complexity and wealth accumulation that required protection.

Residential architecture in Pre-Harappan settlements typically consisted of rectangular mud-brick houses arranged along streets or around courtyards. Houses were generally small and single-storied, with multiple rooms serving different functions. At Banawali, Pre-Harappan houses featured mud-brick construction with sizes measuring 12×24×36 cm or 13×26×39 cm. These structures often included features such as circular pit silos for grain storage and tandoors (ovens) for cooking, both above and below ground level. The presence of specialized storage facilities indicates agricultural surplus and possibly emerging social stratification.

Another characteristic feature of Pre-Harappan architecture is the early development of water management systems. At sites like Kalibangan, baked bricks were used in drains, demonstrating an concern with sanitation that would become a hallmark of mature Harappan cities. While not as extensive or sophisticated as the drainage systems of later periods, these early installations represent important precursors to the advanced hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley Civilization.

The architectural remains also reveal evidence of craft specialization and ritual practices. At Mehrgarh, one of the earliest Pre-Harappan sites, excavations have revealed evidence of specialized craft areas and possible ritual structures. At Kalibangan, fire altars have been discovered in the Pre-Harappan levels, suggesting ritual practices that may have continued into the mature Harappan period. These features indicate the development of complex social and religious institutions that would characterize later South Asian urbanism.

4 Major Pre-Harappan Sites and Their Architectural Features

4.1 Amri

Amri, located on the western bank of the Indus River approximately 160 km south of Mohenjo-daro, represents one of the most important Pre-Harappan sites and serves as the type-site for the Amri-Nal cultural complex. Excavations at Amri by N.G. Majumdar in 1929 and later by Jean-Marie Casal between 1959-1962 revealed four successive periods of occupation, with the earliest ‘Amrian’ phase dating between 3600-3300 BCE 7.

The architectural remains at Amri show a progression from simple structures to more complex settlements. In the earliest phases (Amri IB), archaeologists found small, contiguous rectangular mud-brick houses divided into small rooms 7. In later phases (Amri IC-D), two types of structures emerged: large rectangular mud-brick houses with lateral doorways, and large rectangular mud-brick structures divided into small units that may have served storage functions, similar to those found at Mehrgarh 7. The settlement also featured public architectural units, including enclosing walls, though these have not been fully excavated 7.

The Amri phase pottery provides important cultural markers, with distinctive red-buff ware, often hand-made and featuring black, brown, and red paint applied in geometric motifs such as checkerboard and sigma patterns 7. Later Amri phase pottery shows more complicated motifs including intersecting circles, fish-scale patterns, and zoomorphic designs 7. These artistic developments paralleled architectural innovations, reflecting a growing cultural sophistication.

4.2 Kot Diji

Kot Diji, located in Sindh province of Pakistan, is the type-site for the Kot Dijian culture and provides crucial evidence for the transition from Pre-Harappan to mature Harappan phases. Excavated by F.A. Khan in 1955, the site dates from approximately 3200-2600 BCE and features impressive fortified settlements.

The architecture at Kot Diji includes a massive defensive wall constructed of stone and mud-brick with bastions, protecting both a citadel and lower town area. This division of settlement space anticipates the more sophisticated urban planning of mature Harappan cities. The construction techniques demonstrate advanced engineering knowledge, with mud-bricks and stones used to create substantial defensive structures that would have required significant labor organization.

The pottery found at Kot Diji includes well-fired red ware and buff ware with paintings of horned deities, pipal leaves, and fish-scale patterns. These decorative motifs show cultural connections with later Harappan art traditions. The Kot Dijian culture extended across a large area encompassing northern Sindh, Punjab, Northwest Frontier, and Cholistan, with 111 identified sites, indicating a widespread cultural complex with shared architectural and artistic traditions.

4.3 Kalibangan

Kalibangan, located on the bank of the Ghaggar River in Rajasthan, India, represents one of the most extensively excavated Pre-Harappan sites and provides crucial evidence for the Sothi-Siswal cultural tradition. First identified by Italian Indologist Luigi Pio Tessitori in 1916-17 and later excavated by B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar between 1960-1969, the site features two main mounds with remains from both Pre-Harappan and mature Harappan periods.

The Pre-Harappan settlement at Kalibangan was fortified with mud-brick walls following a 3:2:1 ratio (30×20×10 cm). The fortification was repaired twice, with the wall thickness increasing from 1.9 meters to 3.7-4.1 meters, suggesting ongoing concerns with defense and the organization of communal labor. Within these walls, houses were constructed using mud-bricks in English bond style, with baked bricks used for drains.

Unique architectural features at Kalibangan include fire altars suggesting ritual practices, and tandoors (ovens) both above and below ground level for cooking purposes. The settlement also had pit silos for grain storage, indicating agricultural surplus and storage management. The streets and lanes were approximately 1.5 meters wide, showing some degree of planning in settlement layout.

The pottery at Kalibangan shows six different ceramic types (A-F), with type A featuring dull red surface with black paintings, type B having red ware with rusticated surface and black paintings, and type C demonstrating more delicate forms. These ceramic traditions would influence later Harappan pottery styles.

4.4 Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh, located in the Kachchi Plain near the Bolan Pass in Pakistan, represents one of the earliest antecedents to Pre-Harappan cultures, with occupation dating from 7000 BCE to 1900 BCE. Excavated by French archaeologist J.F. Jarrige between 1975-1985, the site shows a continuous cultural sequence from early Neolithic times through the Pre-Harappan period and into the mature Harappan phase.

In the earliest periods (I-II, 7000-4800 BCE), Mehrgarh consisted of simple mud-brick structures associated with early agricultural and pastoral activities. By Period III (4800-3500 BCE), the settlement showed evidence of more sophisticated architecture, including fine pottery, refined ornaments, and copper tools. In Periods IV-VII (3500-2000 BCE), Mehrgarh became increasingly similar to Indus Valley sites, with architectural and material culture traits anticipating mature Harappan features.

The significance of Mehrgarh lies in its demonstration of a long, continuous development from early farming villages to more complex settlements that would influence Pre-Harappan and eventually mature Harappan cultures. The architectural and technological innovations at Mehrgarh, including early mud-brick construction, craft specialization, and agricultural practices, provided important foundations for later cultural developments in the region.

Table: Chronological Development of Major Pre-Harappan Sites

| Site | Early Phase (c. 3300-2800 BCE) | Middle Phase (c. 2800-2700 BCE) | Late Phase (c. 2700-2600 BCE) | Transition to Harappan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amri | Small rectangular mud-brick houses | Larger houses with lateral doorways | Storage structures, public architecture | Gradual transition with Harappan elements appearing |

| Kot Diji | Early fortifications | Development of citadel/lower town division | Massive defensive walls with bastions | Clear stratigraphic break before Harappan rebuilding |

| Kalibangan | Mud-brick fortification (1.9m thick) | Reinforcement of walls | Fire altars, specialized storage facilities | Abandonment followed by Harappan reoccupation |

| Mehrgarh | Early agricultural settlement | Craft specialization, copper technology | Similarity to IVC features | Continuous development into Harappan period |

5 Technological and Material Innovations

The Pre-Harappan period witnessed significant technological and material innovations that would later enable the architectural achievements of the mature Harappan civilization. These innovations encompassed several domains including construction materials, building techniques, water management, and craft specialization.

In the realm of construction materials, Pre-Harappan cultures made important advances in mud-brick production. While sun-dried mud-bricks had been used in the region since Neolithic times at sites like Mehrgarh, Pre-Harappan cultures developed more standardized brick sizes and proportions. At Kalibangan, mud-bricks followed a consistent 3:2:1 ratio (30×20×10 cm), anticipating the standardized brick sizes of the mature Harappan period. This standardization suggests the emergence of shared construction knowledge across regions and possibly the development of measurement systems. The controlled production of baked bricks for specific purposes such as drains and bathrooms represents another significant innovation, demonstrating an understanding of different material properties for different architectural functions.

Building techniques also advanced considerably during the Pre-Harappan period. The construction of fortification walls at sites like Kot Diji and Kalibangan required sophisticated engineering knowledge and organizational capacity. These walls often featured bastions for defensive purposes and were periodically reinforced and repaired, indicating long-term planning and communal labor organization. The use of English bond masonry at Kalibangan, where bricks are laid alternately as headers and stretchers, provided greater structural stability and represents an important technical advance in construction methods.

Water management technologies developed significantly during the Pre-Harappan period. While not as extensive as the sophisticated drainage systems of mature Harappan cities, Pre-Harappan sites show early experiments with water control infrastructure. At Kalibangan, baked bricks were used in drains, demonstrating concern with sanitation and water disposal. Although evidence for large-scale water management systems is limited in Pre-Harappan contexts, these early installations established technological precedents that would be dramatically expanded in later periods.

Craft specialization intensified during the Pre-Harappan period, with important implications for architectural development. The production of specialized tools for construction purposes, such as stone blades and copper instruments, facilitated more sophisticated building practices. At sites like Banawali, evidence of copper tools and stone blades suggests the emergence of specialized craftspeople supporting construction activities. Similarly, the production of stone beads from materials like faience, shell, and steatite at Banawali indicates craft specialization that would later characterize Harappan urban centers.

The development of ceramic technology also advanced during this period, with implications for architectural elements. While primarily used for pottery, ceramic production techniques contributed to the development of terracotta architectural elements such as drainage pipes and decorative features. The sophisticated pottery traditions at sites like Amri and Kot Diji, with their fine wheel-made wares and elaborate painted designs, demonstrate technological mastery that could be applied to architectural elements.

These technological and material innovations did not develop in isolation but were part of a broader socioeconomic transformation involving increased agricultural production, expanded trade networks, and more complex social organization. The surplus generated through agricultural intensification supported specialized craftspeople and builders, while growing trade networks facilitated the exchange of technological knowledge across regions. These developments created the necessary preconditions for the architectural achievements of the mature Harappan period.

6 Cultural and Economic Foundations

The architectural achievements of the Pre-Harappan period were underpinned by significant cultural and economic developments that transformed South Asian societies between 3300-2600 BCE. These foundations included agricultural intensification, trade network expansion, social stratification, and cultural integration across regions.

Agricultural practices intensified during the Pre-Harappan period, providing the economic basis for architectural development. At Hakra culture sites, evidence shows the cultivation of wheat, oats, rice, lentil, barley, field pea, and grapes. This diverse agricultural base generated surplus food that could support non-farming specialists, including architects, builders, and craftspeople. The construction of circular pit silos for grain storage at sites like Banawali and Kalibangan indicates both agricultural surplus and developed storage management systems. The ability to store food surpluses enabled communities to withstand seasonal variations and support larger populations, which in turn required more substantial architecture and settlement planning.

Animal domestication played an important role in Pre-Harappan economies, providing not only food resources but also traction power for transportation and construction. At Mehrgarh, the domestication of cattle, sheep, goats, and bulls provided essential resources for early agricultural communities. At Hakra culture sites, animals included cattle, sheep/goat/gazelle, and pig. The availability of domesticated animals, particularly cattle, would have facilitated the transportation of construction materials and provided manure for brick production, supporting architectural activities.

Trade networks expanded significantly during the Pre-Harappan period, facilitating the exchange of materials, technologies, and ideas across regions. The presence of semi-precious stones and metal artifacts at Amri phase sites indicates interaction with other social groups in the Indus Valley and Baluchistan 7. Similarly, the similarity between Sothi pottery and examples from Baluchistan (Kille Ghul Mohammed, Kechi Beg) suggests long-distance cultural connections. These exchange networks allowed for the dissemination of architectural knowledge and technologies across regions, contributing to the development of more sophisticated building traditions.

Social organization became increasingly complex during the Pre-Harappan period, with implications for architectural development. The construction of fortification walls at multiple sites suggests the emergence of political authorities capable of organizing communal labor for defensive purposes. The appearance of specialized craft products such as stone beads, copper objects, and fine pottery indicates the development of occupational specialization and possibly social stratification. These socioeconomic changes created both the need for more substantial architecture and the organizational capacity to construct it.

Cultural practices and belief systems also evolved during this period, influencing architectural forms. The presence of fire altars at Kalibangan suggests ritual practices that required specialized architectural features. Similarly, the development of distinct ceramic traditions with decorative motifs such as horned deities, pipal leaves, and fish-scale patterns at Kot Diji indicates cultural concepts that might have been expressed in architectural ornamentation. These cultural developments created contexts for architectural innovation that served both practical and symbolic functions.

The integration of diverse regional traditions was another important feature of the Pre-Harappan period. The similarities between pottery styles and architectural forms across different regions suggest increasing cultural contact and exchange. For example, the presence of Amri-Nal, Kot-Diji pottery in Gujarat sites like Dholavira indicates cultural connections between geographically separated regions. This cultural integration created the foundation for the more uniform traditions of the mature Harappan period.

Table: Economic Foundations of Pre-Harappan Architecture

| Economic Sector | Developments | Impact on Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Diversification of crops (wheat, barley, rice, lentils); development of irrigation; grain storage systems | Generated surplus to support specialized builders; enabled larger populations requiring more substantial architecture |

| Animal Husbandry | Domestication of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs; use of animals for traction | Provided transportation for construction materials; manure for brick production; secondary products for trade |

| Craft Specialization | Production of stone tools, copper objects, pottery, beads | Developed tools for construction; produced decorative elements for architecture; generated wealth for architectural projects |

| Trade Networks | Exchange of materials (stones, metals), technologies, and ideas across regions | Facilitated dissemination of architectural knowledge; access to non-local building materials |

7 Transition to the Mature Harappan Phase

The transition from Pre-Harappan to mature Harappan phases represents a crucial transformation in South Asian history, marked by significant changes in architectural styles, urban planning, and material culture. This transition occurred around 2600 BCE and involved processes of cultural integration, technological refinement, and urbanization that built upon Pre-Harappan foundations while introducing new elements.

The transition process varied across different regions, with three distinct patterns evident in the archaeological record. At some sites, such as Kot Diji and Kalibangan, there was a clear stratigraphic break between Pre-Harappan and Harappan levels, suggesting possible abandonment or disruption before reoccupation. At other sites, including Amri and Harappa itself, the transition appears more gradual, with a continuous development from Early to Mature Harappan phases. A third pattern is evident at sites like Banawali, where the stratigraphic break is not clearly marked, and a situation of overlap exists between Pre-Harappan and Harappan material culture 6.

Architecturally, the transition to the mature Harappan phase saw the standardization of building practices across a vast area. While Pre-Harappan architecture showed significant regional variation, mature Harappan architecture developed more uniform characteristics, including consistent brick sizes (4:2:1 ratio), standardized city plans with grid patterns, and sophisticated drainage systems 5. This standardization suggests greater cultural integration and possibly more centralized political control over construction practices.

Urban planning became more sophisticated during the transition to the mature Harappan phase. The division between citadel and lower town areas, seen in nascent form at Pre-Harappan sites like Kot Diji, became a defining feature of mature Harappan cities such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. The grid pattern of streets, evident in preliminary form at Pre-Harappan Kalibangan, became more regularized and consistent in mature Harappan settlements. These developments represent the refinement and standardization of urban planning principles that had emerged during the Pre-Harappan period.

Construction technologies advanced significantly during the transition period. The use of baked bricks became more widespread, particularly for drains, bathrooms, and defensive structures 5. Water management systems became more sophisticated, with extensive networks of drains, wells, and bathing platforms 5. The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro, with its ingenious hydraulic system, represents the culmination of water management technologies that had their origins in Pre-Harappan experiments with drainage and bathing facilities 4.

The expansion of trade networks during the transition period facilitated the exchange of architectural ideas and technologies across regions. The similarity between mature Harappan architectural elements at sites as far apart as Dholavira in Gujarat and Shortugai in Afghanistan suggests efficient communication and exchange systems 6. These networks built upon Pre-Harappan trade connections but operated on a larger scale and over greater distances.

Social organization became increasingly complex during the transition to the mature Harappan phase. The construction of massive public structures such as the Great Bath and granaries at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa suggests the emergence of authorities capable of organizing labor on a large scale 45. The standardization of weights and measures across the Harappan cultural zone indicates economic integration and possibly administrative control 6. These developments enabled the coordination of architectural projects that exceeded the scale and complexity of anything achieved during the Pre-Harappan period.

Despite these significant changes, important continuities existed between Pre-Harappan and mature Harappan architectural traditions. The basic mud-brick construction techniques, the concern with water management and sanitation, and the orientation of settlements along cardinal directions all show clear links between earlier and later periods. These continuities demonstrate that the mature Harappan civilization did not emerge ex nihilo but built upon technological and cultural foundations established during the Pre-Harappan period.

8 Conclusion: Significance of Pre-Harappan Architectural Traditions

The architectural traditions of the Pre-Harappan period represent a crucial chapter in the history of South Asian urbanism, providing important foundations for the subsequent development of the Indus Valley Civilization. Through examining these early architectural achievements, we gain insight into the processes of technological innovation, cultural development, and social complexity that enabled the emergence of one of the ancient world’s most sophisticated urban civilizations.

The significance of Pre-Harappan architecture lies in its role as a laboratory for experimentation with forms, materials, and techniques that would later characterize mature Harappan cities. The development of standardized mud-brick production at sites like Kalibangan established technical precedents for the uniform brick sizes of the Harappan period. Early experiments with water management systems, including drains and bathing platforms, anticipated the sophisticated hydraulic engineering of cities like Mohenjo-daro. The emergence of fortification systems at multiple sites reflected growing concerns with defense and territorial control that would continue in later periods.

Pre-Harappan architecture also demonstrates the cultural diversity and regional variation that characterized northwestern South Asia before the relative uniformity of the mature Harappan period. The distinct traditions of the Amri-Nal, Kot Dijian, Sothi-Siswal, and Hakra cultures show different adaptations to local environments and resources. This regional diversity gradually gave way to greater cultural integration, but it contributed important elements to the synthesis that would become the Harappan civilization.

The study of Pre-Harappan architecture provides valuable insights into the social organization of early South Asian communities. The construction of substantial fortification walls and public structures required communal labor organization and suggests the emergence of political authorities capable of coordinating such projects. The evidence for craft specialization and trade indicates developing economic complexity that supported architectural development. These socioeconomic changes created the necessary conditions for the urban revolution that would follow.

From a broader comparative perspective, Pre-Harappan architecture represents an important case study in the early development of urban traditions. Unlike Mesopotamia and Egypt, where urbanism emerged through processes that are still imperfectly understood, the developmental sequence in South Asia is particularly well-documented through sites like Mehrgarh, which shows a continuous sequence from early Neolithic villages to Pre-Harappan settlements. This extended sequence provides valuable evidence for understanding the gradual processes through which simple villages evolved into complex urban centers.

The legacy of Pre-Harappan architecture extends beyond the Indus Valley Civilization to influence later South Asian architectural traditions. Elements such as the concern with water management, the use of mud-brick construction, and the orientation of buildings along cardinal directions persisted in South Asian architecture for millennia. The fire altars found at Kalibangan anticipate later Vedic ritual practices, suggesting religious continuities spanning multiple millennia. These enduring influences demonstrate the profound impact of Pre-Harappan architectural innovations on South Asia’s cultural development.

In conclusion, the Pre-Harappan period represents a formative era in South Asia’s architectural history, during which important technological, cultural, and social foundations were established for the urban revolution that would follow. The architectural remains from this period provide valuable evidence for understanding the processes through which simple villages evolved into complex urban centers. Through continued archaeological investigation and analysis, our understanding of this crucial period will undoubtedly deepen, providing further insights into the origins of South Asia’s urban tradition.