Buddhist ideals. Elucidate.

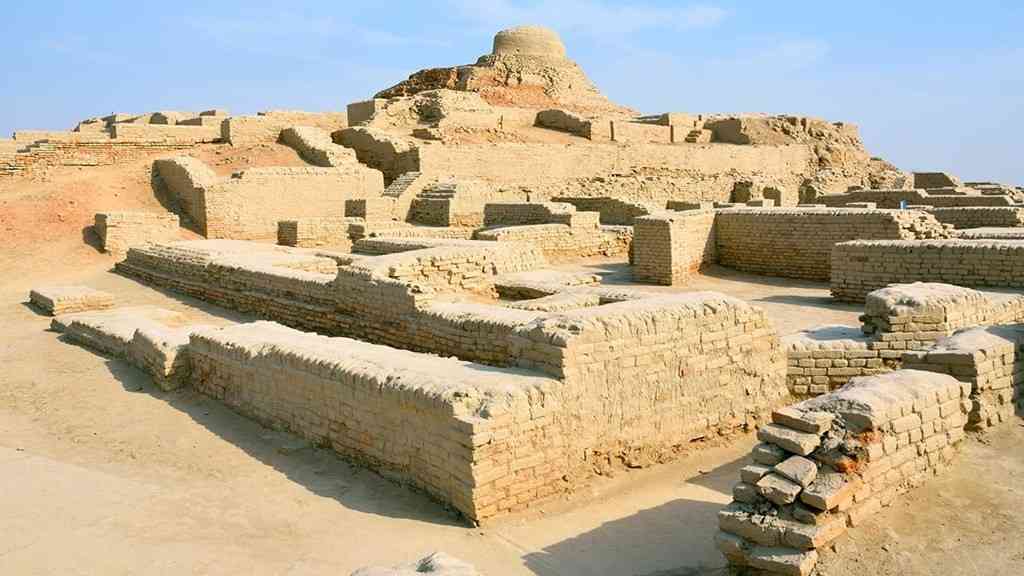

Picture Attributes to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanchi

Introduction

Buddhist stupa art plays a significant role in the visual culture of early Buddhism, both as a form of religious expression and as a vehicle for communicating Buddhist philosophical ideas. The stupa itself, a dome-shaped structure that enshrines relics of the Buddha, serves as a focal point for Buddhist worship and meditation. Stupa art, which surrounds and decorates these sacred spaces, uses visual imagery to reflect the teachings and ideals of Buddhism.

In early Buddhist art, particularly in stupa decoration, the absence of the direct depiction of the Buddha’s image is notable. Instead, artists used symbolic representations such as the Buddha’s footprint, the tree under which he attained enlightenment, or the wheel of dharma. These symbols convey the essence of the Buddha’s teachings while maintaining an abstracted approach, suitable for the religious context.

The early Buddhist stupa not only represents physical space but also encapsulates spiritual principles such as impermanence, suffering, and the path to enlightenment. Folk motifs—elements from the daily life and local traditions—were incorporated into these spaces to make the teachings accessible to a wide audience. These motifs act as a bridge between the religious ideals of Buddhism and the cultural context in which the art was created.

This essay seeks to explore how early Buddhist stupa art, while depicting folk motifs and narratives, successfully expounds Buddhist ideals. By analyzing the symbolic and narrative content of early stupa reliefs and sculptures, we will see how these elements are not merely decorative but serve as a form of visual discourse that teaches the Buddhist path.

The Evolution of Buddhist Stupa Architecture and Art

The stupa, as both an architectural and artistic form, evolved from pre-Buddhist burial mounds found in India. Initially, stupas were simple earthen mounds covering the relics of important figures. The evolution of the stupa into a more complex structure mirrored the development of early Buddhist teachings, which sought to communicate the Buddha’s presence through sacred architecture.

The core feature of the stupa is its dome, or “anda,” which symbolically represents the universe. Atop the dome is a central pillar, or “yasti,” representing the Buddha’s spiritual axis. Surrounding the stupa are railings and gateways that symbolize the teachings of the Buddha as paths to enlightenment. The design of the stupa reflects a universe that is ordered and harmonious, which corresponds to the Buddhist belief in the cosmos’ interdependent nature.

Early stupa art, found in places such as Sanchi and Bharhut, transformed the stupa from a simple reliquary into a space of worship and spiritual instruction. Artists began to decorate the railings, gateways, and even the dome with reliefs that illustrated important moments from the Buddha’s life and teachings. These artworks serve both a decorative and didactic function: they bring the religious teachings to life for the viewer, allowing them to connect with the stories and lessons of the Buddha through visual means.

The stupa, therefore, is not just an architectural space but a symbolic representation of the Buddhist cosmos and a physical embodiment of the Buddha’s presence in the world. Through the careful integration of architectural and artistic elements, early stupas communicated profound spiritual concepts, making the teachings of Buddhism accessible to all.

Folk Motifs in Early Buddhist Stupa Art

Folk motifs in early Buddhist stupa art are not simply decorative elements; they play an essential role in conveying Buddhist ideals to a wider audience. Folk art, with its roots in everyday life and local cultural traditions, was a means by which Buddhist ideas were made accessible to those who were not familiar with the sophisticated philosophical texts of Buddhism. These motifs were familiar to the local populations, making Buddhist teachings more approachable and relatable.

Common motifs such as animals, plants, and celestial beings appear frequently in stupa reliefs. For example, elephants are symbolic of the Buddha’s mother and are often depicted as nurturing figures, associated with purity and wisdom. Lions, on the other hand, are frequently shown in Buddhist art as representations of courage and strength, symbolizing the Buddha’s lion-like roar in his teachings. Other animals like horses, deer, and birds were also commonly depicted, each carrying their own symbolism within the Buddhist context.

Additionally, natural elements such as trees, flowers, and the lotus are used in stupa art to symbolize the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The lotus, in particular, is an enduring symbol of purity and enlightenment, as it grows out of the murky waters but rises above to bloom, free from contamination. These symbols provide visual metaphors for the Buddhist path to enlightenment, where one overcomes the “mud” of ignorance and suffering to attain purity and wisdom.

These folk motifs are not only symbolic in the Buddhist context but also integrate the religious beliefs of the local communities. The fusion of Buddhist ideology with local cultural elements made the teachings of Buddhism more palatable and comprehensible to people from various backgrounds. Thus, folk motifs in stupa art act as a cultural bridge, connecting the Buddhist teachings to the everyday lives of the people.

Narratives in Early Buddhist Stupa Art

The use of narrative in early Buddhist stupa art is a key way in which the teachings of Buddhism were communicated. These narratives often focus on the life of the Buddha, depicting key events such as his birth, enlightenment, and parinirvana (final liberation). The Buddha’s life is presented not as a series of isolated incidents but as a profound journey of spiritual development that reflects the central Buddhist ideals of wisdom, compassion, and the overcoming of suffering.

One of the most significant aspects of early Buddhist stupa art is the absence of the Buddha’s direct image in many reliefs. Instead, his presence is often suggested through symbolic representations, such as his footprints or an empty throne. These symbols emphasize the transcendence of the Buddha, who, after reaching enlightenment, is no longer bound by the physical world. The focus, then, is on his teachings and the path he showed to others, rather than on his physical form.

The Jataka tales, which recount the Buddha’s previous lives as a bodhisattva, also form a key component of the narrative content of early stupa art. These tales illustrate the virtues of the Buddha in his past incarnations, emphasizing values such as generosity, compassion, and patience. Through these stories, stupa art provides moral lessons that align with Buddhist teachings. The Jataka tales often feature animals, humans, and deities in stories that highlight the importance of ethical conduct and the gradual progression toward enlightenment.

The narrative style in early stupa art was not just intended to tell a story but to serve as a tool for teaching Buddhist values. The visual representation of these stories makes the complex philosophical teachings of Buddhism more accessible to a broader audience, especially in a time when many people could not read or write.

Buddhist Ideals Reflected in Stupa Art

Early Buddhist stupa art is rich with symbolic imagery that conveys the central teachings of Buddhism, such as the concepts of nirvana, the Four Noble Truths, and karma. Each element in the stupa’s design, from the architecture to the narrative reliefs, reflects these foundational principles.

Nirvana: The ultimate goal in Buddhism is to attain nirvana, a state of liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara). Early stupa art, with its symbolic use of the Buddha’s absence and the focus on representations of his teachings, reflects this goal of transcendence. The stupa itself can be seen as a representation of the Buddha’s spiritual presence, encapsulating the idea that nirvana is not a physical state but a state of inner peace and understanding that transcends worldly suffering.

The Four Noble Truths: These fundamental Buddhist teachings—the truth of suffering (dukkha), its cause (tanha or craving), the cessation of suffering, and the path leading to the cessation of suffering—are often visually represented in early stupa art. For example, scenes depicting the Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi tree symbolize the realization of these truths, while other reliefs may illustrate the Buddha’s teachings on overcoming attachment and desire.

Karma: Karma, the principle that actions have consequences, is another core concept reflected in early stupa art. Many reliefs in stupa architecture depict scenes from the Jataka tales, showing the Buddha’s past lives and the consequences of his actions, whether good or bad. The concept of moral cause and effect is central to the Buddhist worldview, and these stories visually reinforce the idea that one’s actions determine their future spiritual progress.

The ideals of compassion, wisdom, and ethical conduct are interwoven into the art and symbolism found in early stupas. By illustrating these teachings, stupa art serves not only as a means of worship but also as an educational tool, offering viewers a visual representation of the Buddhist path to enlightenment.

Symbolism in Stupa Art: The Use of Sacred Objects and Geometry

The symbolic use of sacred objects and geometry in early stupa art is a key feature of its design. These elements are not merely ornamental but are deeply connected to Buddhist cosmology and the teachings of the Buddha.

Sacred objects such as the wheel of dharma, the lotus, and the stupa itself carry profound spiritual meanings. The dharma wheel, for example, represents the teachings of the Buddha and the turning of the wheel of time, signifying the spread of his message. The lotus symbolizes purity and enlightenment, as it rises above the murky waters of samsara to bloom free from contamination. The stupa, as a whole, is a microcosm of the universe and a representation of the Buddha’s enlightenment and teachings.

The geometry of the stupa, with its circular form and careful spatial organization, also reflects the Buddhist view of the cosmos. The stupa’s design is often based on sacred geometry, with proportions that mirror the cosmic order. The central pillar, or yasti, is seen as a representation of the axis of the world, and the circular form of the stupa symbolizes the cyclical nature of existence and the universe.

Through the careful use of sacred symbols and geometry, stupa art invites the viewer to contemplate the deeper spiritual truths of Buddhism, offering a visual map to the path of enlightenment.

The Interaction of Folk and Buddhist Elements

The integration of folk elements into early Buddhist stupa art allowed the teachings of Buddhism to resonate with local populations. By incorporating familiar symbols and motifs from everyday life, early Buddhist artists ensured that the art was accessible to a broad audience, including those who may not have been well-versed in Buddhist philosophy.

This interaction between folk and Buddhist elements is seen in the use of local deities, animals, and mythological figures, which were reinterpreted within the Buddhist context. For example, the horse, a common symbol in Indian mythology, was adapted to represent the Buddha’s teachings about the nature of desire and the importance of overcoming attachments.

By using these local elements, Buddhist art became more relatable and comprehensible, allowing people from different regions and cultural backgrounds to connect with the universal principles of Buddhism.